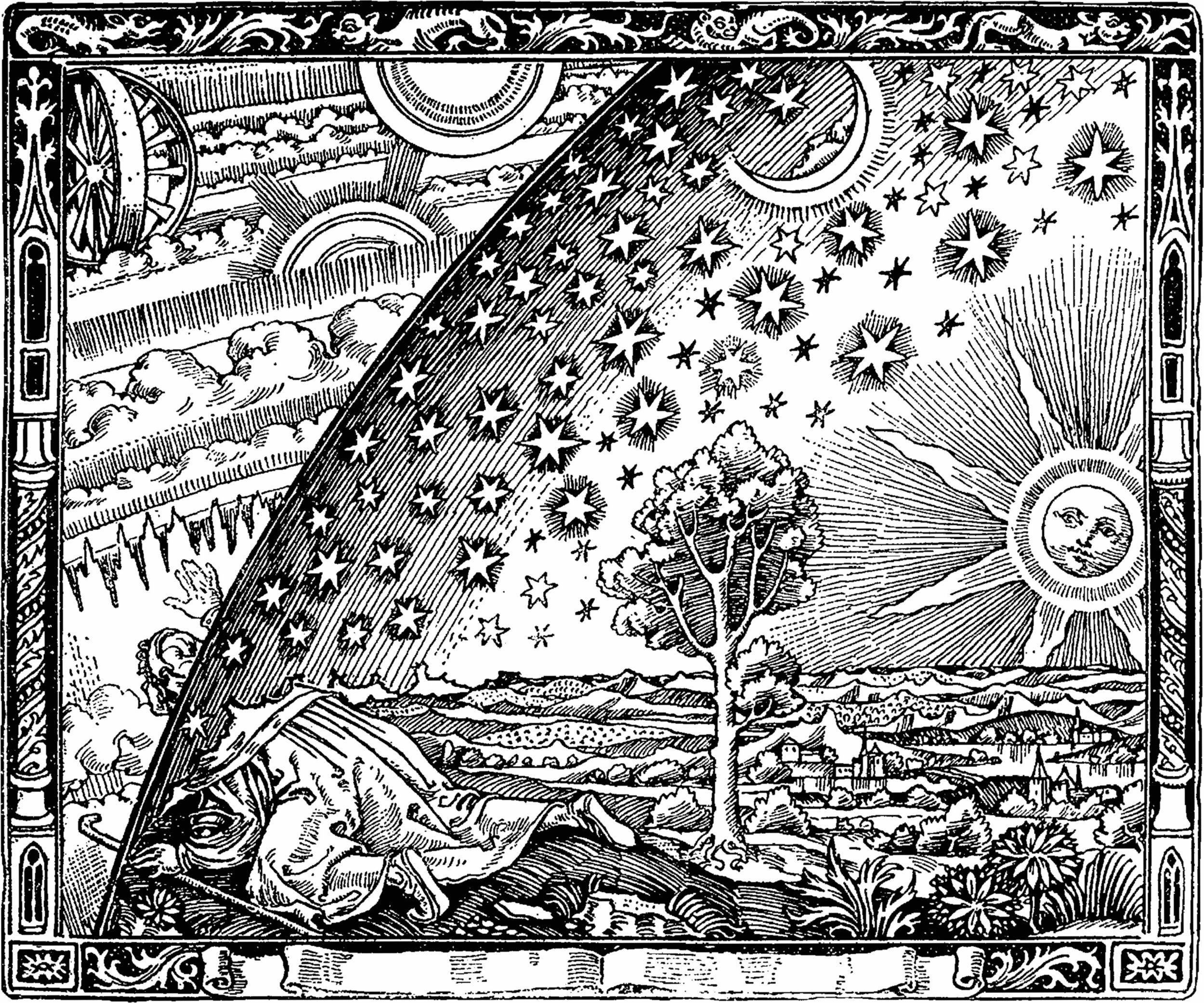

The thought hardly ever occurs to us that humble household items have the power to astonish and shape our world beyond our expectations. These objects, formed through mental and physical efforts, have the power to show us the way the world really is. Throughout history the idea of chaos has been exemplified in the image of the sea. It is a roiling surface that never settles and hiding what lies beneath. Although we do not know exactly what may be beyond that turbulent surface, we expect to find malevolence there. In Ancient cosmologies the chaos, like the sea, was extensive, so much so that it encompassed the world. The heavens were pictured as an upturned bowl where stars sat encrusted and protecting from the uncertainty of the surrounding chaos.

Camille Flammarion in L’Atmosphère: Météorologie Populaire

To a lesser extent, the ancients saw the natural and uncultivated world as chaotic. The cultivated world was everything that had been subjected to human knowledge and manipulation. Knowledge is the means by which we draw boundaries around things and ideas, isolating them from their natural context in the world. The designed world is the embodiment of knowledge in action. In the context of these cosmologies the bowl came to stand for something that could tame and cultivate even the paradigm of chaos in a way that other things cannot. It can isolate a small region of this chaos and make it captive to knowledge and human desire.

A designed object is the result of an imposed order or structure brought about by thought and action. Order can be imposed on mental and physical objects. We order thoughts in our minds putting them down on a page and in like manner, we impose order on physical things such as bricks arranged into building. Order in this sense comes from mind as it is both intentional and purposeful. If this order shows the presence of a mind, then chaos is the absence of a mind. We look at the world we have cultivated and see an order that unambiguously shows the presence of a mind. In our quiet moments we also see an order to the uncultivated, natural world.

Bowl and bowl fragments with an S profile in Oross, K., “The pottery from Ecsegfalva 23”

The Evolutionary Biologist Richard Dawkins described biology as “the study of complicated things that give the appearance of having been designed for a purpose”.* Modern evolutionary theory explains the seeming structure behind the world by positing a set of natural principles that give rise to order. Why these natural principles should exist is a mystery yet to be solved. It is easy to see how order could come out of chaos through the actions of a mind. It is not so easy to see how order could come out of chaos spontaneously and consistently without a mind. Order may give way to chaos but chaos, on the other hand, must be structured through thoughts and action to create order. In this sense order is something outside of the physical world because it is of mind. Where a mind rules we can expect stability and regularity; we expect order. This was the founding principle behind modern sciences and the driving force behind the tools of the scientific method. The early scientists described a world that was regulated by the thoughts of a rational mind and a ‘law-giver’.

Glacially created bowl of Llyn Cau. Photograph by Flickr user Andrew

G.K. Chesterton once quipped that the pagans got a lot wrong about the physical world around them but not that the world may be somehow personal. In a totally chaotic world, there is dread and constant fear of nature due it being impersonal and unpredictable. If, however the chaos might be controlled and manipulated by rational minds, then the world takes on a different meaning.

Why is the sense of imposed structure or order behind the world so comforting? Evolutionary theory has a definite appeal because it presents a way to tame the chaos. The evolutionary myth** is that the natural world that surrounds us is structured by invisible forces moving things in the right direction at the right time to produce what we see today. We come to see that the world is really more deterministic than we realise and therefore the chaos is imaginary. Why is it that Dawkins can be an intellectually fulfilled atheist?*** The evolutionary myth makes sense of the uncertainty in the world and staves off the idea that it may be chaotic.

Design has a similar appeal because it can also tame the uncertainty in the world around us by cultivating it. In contrast to a world cultivated by design, a chaotic world is functionless. If chaos ever provides any meaningful function it must be purely accidental as it lacks forethought. Such a world is impossible for us to live in without it being formed into a habitable place. Perhaps our modern world is so obsessed with design because it is the ultimate form of control. It shows that we have mastered the chaos around us through our mental and physical efforts.

Chaos depends on the uncertainty we observe in the world, manifesting itself in confusion and ultimately malevolence. Although uncertainty does not always give way to our worst fears, it sometimes gives way to reveal something genuinely good. This is where we uncover wonder.

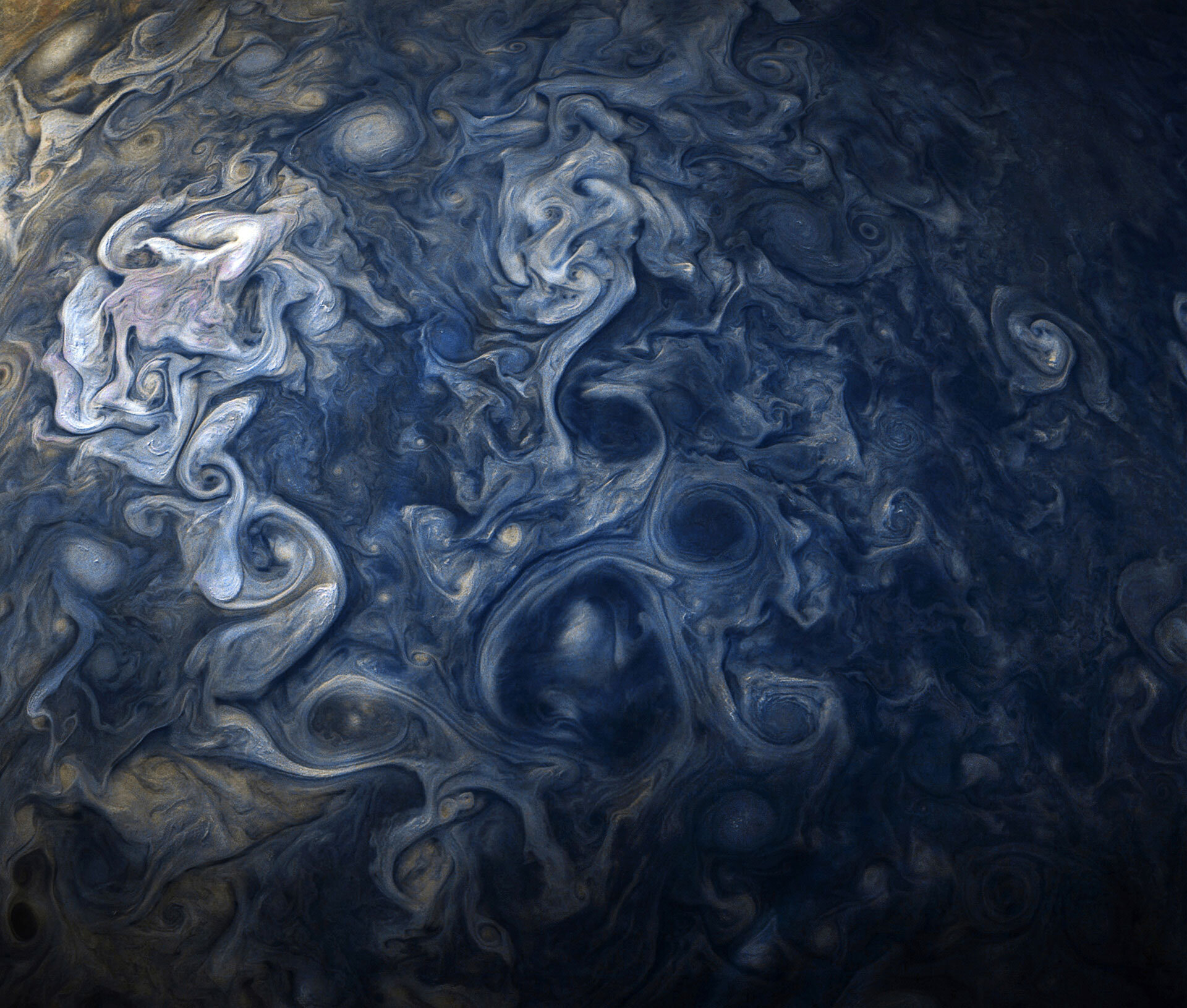

Chaotic Jovian clouds on Jupiter’s surface by NASA

We experience some uncertainty whenever we encounter wonder. It is that sense of benevolence that hides behind or beyond things. Perhaps it takes us by surprise because we can hardly predict when we might encounter it. It is startling and even more, it fills us with joy. Both wonder and chaos are related to a sense of uncertainty. We may call uncertainty the line drawn between malevolence and benevolence; on the one side is chaos and on the other is wonder. Wonder is often accompanied by a sense of awe; a sense of our smallness that both humbles and makes us grateful. For a thing to be wonderful it must expand our vision of the world. The Greek word ’ekstasis’ describes the state of being outside oneself. In ecstasy we forget about ourselves, which allows us to see and appreciate things in ways that are otherwise unavailable to us.

Our sense of wonder at the world has little to do with size. Instead it comes from the expansiveness of our view of the world and how far removed we are from ourselves. There are small wonders and much larger ones; we can be equally amazed at the universe and a blade of grass.

Wonder is sometimes uncovered from behind what may seem to be certain, while chaos seems to occupy the shifting surface of uncertainty. In wonder the familiar is uncovered and made into something very unfamiliar; uncertainty gives way to underlying order. The key here is that our world is expanded through wonder. It is not simply bigger but more expansive; that is, it appears bigger than we could have imagined it to be. In this sense, wonder is a much deeper thing than chaos.

The ancient Greeks used the word ‘logos’ to describe the ordering principle or logic behind the world. If the world is imbued with logos, then it is not really a chaotic place. Rather it has a deeper underlying structure which we may uncover. In this sense wonder is closely related to truth; it can show us the reality behind things and the way they really are. The truth uncovers the logos or underlying principles that undergird reality.

James Turrell’s Skyspace. Photograph by Phil Blackburn

Objects that allow us to wonder are those that allow us to look through them and we see the world around us like never before. James Turrell’s Skyspaces are a good example of this. They present what is common and familiar to us in a way that we have never seen or considered. In one of his many Skyspaces an odd optical illusion makes the distance between the viewer and sky seem dramatically reduced. Against the backdrop of the oculus the sky appears to be in the same plane as the ceiling of the space. With the distance between us and the sky reduced, we are able to observe subtle changes in the sky and see it as never before. The heavens are no longer an upturned bowl holding back the surrounding chaos. In the Skyspace we are transported closer to it. We get the sense we have tamed a portion of the sky, like cupping sea water in our hands.

Detail of James Turrell’s Skyspace. Photograph by Tom Parnell

The depth of our wonder at a thing depends on the distance between what is apparent (what lies on the surface) and what is uncovered (what lies behind the surface). The idea of beauty, goodness and truth are at the heart of wonder. Beauty is either revealed or magnified when we experience wonder. Although we may desire to possess a beautiful thing, it inevitably possesses us by drawing us out of ourselves. There is a sense that truth is layered; we could always go deeper. Wonder is the uncovering of a deeper truth. Truthful and beautiful things are by their nature good, because they show us the world as it is. In wonder, the world appears to be a better place than we could have imagined. In wonder our sense of malevolence is subdued and replaced by joy and hope; joy because the world is good and hope because we cannot help but see and desire a future without malevolence.

Uncertainty is impenetrable to the degree we are unaware of truth and its mastery through order. Chaos dwells on the surface of uncertainty, while wonder is always uncovered. Chaos imposes itself on us, while we must seek out wonder. Wonder is good because it empowers us as truth seekers and rewards our curiosity. Wonder is ecstatic, drawing us out of ourselves. Both wonder and chaos contain a sense of uncertainty, because we do not know what to expect. Wonder uncovers goodness, beauty and truth if only we would pay attention.

Bowl by Tad Spurgeon

* Dawkins, R., The Blind Watchmaker (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2015), p.4.

** The word myth is used in the sense of a story told to explain the world as we know it, rather than in the sense of an untrue story.

*** Dawkins, R., The Blind Watchmaker (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2015), p.10.